By Erika Pettersen, independent researcher, strategist, resource builder, and creative writer

I want to begin by sharing my own personal and professional journey, which led me to author a report titled Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector.

As fundraisers, many of us can relate to being drawn in by a cause near and dear to our hearts—and tripping into development work as a result.

Because someone tells us we’d be good at it. Because it pays a little better than other nonprofit roles. Because we see the need.

Then, somewhere along the line, we reach a state of cognitive dissonance.

On the one hand, we believe we can change the world for the better through the organizations we work for. On the other, our development responsibilities often compel us to perpetuate the very power dynamics that undergird the economic and racial inequities we seek to overturn.

Before the Community-Centric Fundraising (CCF) movement took root, it was hard, if not impossible, for many of us to even articulate this phenomenon, let alone address it. We grew cynical. We lost faith. We burnt out.

Now, through CCF, we’re learning how to boldly name the ways in which traditional fundraising upholds oppressive white supremacist hierarchies and devising strategies for evolving fundraising into a praxis that more fully aligns with our values and goals.

Taking root within a nonprofit sector addressing a diversity of societal issues, CCF builds on a variety of histories and lived experiences. Each and every one of us brings unique and special insight into the past, present, and future of this movement. Drawing on both my lived experiences and my action-oriented research, this three-part series of essays will dive into some of the particular challenges, opportunities, and questions for CCF brewing within the arts and culture field.

In this first essay, I want to begin by sharing my own personal and professional journey, which led me to author a report titled Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector.

The Personal is Political

Growing up in Jackson Heights, Queens, where over 150 languages are spoken, and half the population are immigrants, I’d assert my multi-ethnic identity with pride—and mathematical precision: “I am ¼ Ecuadorian, 3/8 Irish, 1/8 Norwegian, and ¼ Puerto Rican.” Slowly, though, the fractions started to work on me. Although my mixed background felt like a perfect match to my neighborhood, I was unsure what my identity actually added up to.

I also came to understand that the diversity of Jackson Heights was an anomaly, even within New York City. First, through stories from my mother about her childhood in the South Bronx, and later, when I worked in similarly segregated areas of the city, the socio-economic consequences created by these divisions became apparent to me. Working with a national nonprofit as an AmeriCorps volunteer in Harlem, I grew impatient with our efforts to connect residents with public benefits and low-paying jobs. Simply managing the repercussions of redlining and disinvestment felt myopic in the face of enduring structures that maintain racial inequities in the U.S.

Subsequently, I sought to follow the lead of geographic and cultural communities most impacted by the literal and figurative lines drawn by white supremacist systems of power. Working with Black-led nonprofits serving Brooklyn communities subject to damaging mainstream narratives, I became passionate about supporting their efforts to amplify arts and culture in ways that laid claim over their collective stories.

As fundraising became more central to my job responsibilities, a familiar frustration crept up on me. The fact that funding depended on meeting standards set by wealthy and largely white decision-makers, far removed from the lived experiences of the communities these organizations served, seemed to undermine the paradigm-shifting nature of this work. By 2018, after nearly a decade in the nonprofit sector, I was exhausted by the nonprofit development hamster wheel and disillusioned by the larger political environment wherein white supremacy was on unabashed display. It felt urgent to pause and reflect.

So, I went back to school.

Entering the Latin American Studies Master’s program at Tulane University, a particular Trumpian tautology haunted me: “We either have a country or we don’t have a country.” I pondered the deliberate divides—physical, social, and ideological—drawn by this statement, along with its foregone conclusion that our world depends on the policing of borders between lands, communities, and ways of life.

Considering Latin America—the region this statement called to wall off—I also looked inward at the unreconciled map of my own mixed European and Latina heritage. These disquietudes guided my studies on the politics of identity, belonging, and representation at the intersections of culture, race, and gender. My thesis centered on how women in Oaxaca, Mexico access opportunities to destabilize hegemonic constructions of Indian womanhood, counter marginalizing discourses, and create visibility for Indigenous and Afro-descendent Mexicans to assert, validate, and advocate for their own values and ways of life.

Through this research, I graduated with a deeper understanding of the transnational white supremacy culture that oppresses Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (POC), along with how it produces its power and compels our complicity through systems designed to perpetuate marginalization and exploitation.

Bridging Theory and Practice

I came out of graduate school during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Racial inequities in the United States had become even more transparent and undeniable, but I felt more fully equipped to wrestle with them.

In 2021, a friend and former colleague from my time as Development and Communications Director at Haiti Cultural Exchange recruited me to join her on the research team at Arts Business Collaborative (ABC). While the research department at ABC was short-lived, officially phasing out in September 2023, my brief time there offered an exceptional window of opportunity to connect my graduate studies to my professional history as a fundraiser.

The CCF movement had gained incredible momentum during my hiatus from the nonprofit sector. I was blown away by the boldness and thoroughness with which the founders of CCF took aim at donor-centric fundraising practices. They had translated the tensions and misgivings so many of us fundraisers and nonprofit staff have felt over the years into dynamic critiques of and actionable responses to the racial and economic inequities created by power imbalances in philanthropy’s white supremacist systems and structures.

I was eager to dig into the impact of CCF on the nonprofit sector and pitched an exploratory study on CCF in the arts and culture sector. ABC leadership gave me the green light to design and execute an exploratory study on CCF in the arts.

I centered this project on interviews with twenty arts and culture resource builders1, most of whom identified as POC and/or as working for a POC-led arts organization in the U.S. Our conversations were provocative and unbelievably awe-inspiring, exploring countless facets of CCF and the larger arts and culture philanthropy landscape.

Amidst these diverse discussions, two core themes emerged. Firstly, research participants offered insights and questions exploring the “why” of CCF, or the movement’s overarching vision for systemic change. Secondly, they shed light on and sought greater clarity on the “how” of CCF, or what the movement’s work looks like in practice. I also engaged in a supplemental literature review prior to, during, and following interviews. As participants’ interest in the “why” and “how” of CCF became clear, these themes guided my exploration of relevant media and text.

Racial Inequities in Arts & Culture Funding

By analyzing the funding landscape for arts and culture organizations, I found that the nonprofit sector largely perpetuates the arts labor exploitation, financial insecurity, and racial inequities created by capitalism.

A survey conducted by Arts Funders Forum in 2019 reports that 78% of respondents indicated that they were “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned” about the future of arts funding.2 These concerns are supported by reports from Grantmakers in the Arts (GIA) that demonstrate declines in institutional funding for arts and culture when accounting for inflation.3 Dwindling support erodes at an already meager share of philanthropic dollars, with arts, culture and humanities only receiving 5% of overall US giving.4

Above and beyond the sector-wide economic insecurity, POC nonprofits are subject to a phenomenon called “philanthropic redlining,” which the Memphis Music Initiative (MMI) defines as:

A set of funding practices in which an organization’s size, racial or ethnic constitution, demographic served, artistic designation (e.g., “high art” or “community art”), and/or location results in: (a) exclusion from funding altogether, (b) grants that are substantially lower than comparable organizations; and/ or (c) forms of funding that discourage capacity building.5

The extension of redlining into philanthropic practices causes astounding racial inequities in arts and culture funding.

Of 925 US cultural organizations with budgets over $5 million, fewer than 50 are dedicated to POC artistic traditions and/or communities. Moreover, in 2017, when POC constituted 37% of the US population, only 4% of private philanthropy going to arts and culture went to POC-serving organizations. Even where POC-serving nonprofits made up 25% of local cultural groups, these organizations received a mere 10% of local cultural funding. 6

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the tide appeared to be turning in response to a racial reckoning in the US catalyzed by the oversized toll on public health faced by POC communities as well as the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by law enforcement officers. In fact, GIA reported that 51% of grantmakers they surveyed in 2020 indicated that they’d increased giving to POC-led organizations.7 Still, only $3.4 billion of a total $11.9 billion that was pledged to racial equity work in 2020 was confirmed to have been actually awarded by October 2021.8

The “Crisis of Relevancy” and the Nonprofit Industrial Complex

Contextualizing racial equity issues in nonprofit funding within the arts and culture field’s wider struggles to secure an adequate share of philanthropic dollars guided my research on CCF to address philanthropic dialogue regarding the social impact of the arts.

In her conversation series “The Path Forward,” cultural philanthropy advisor Melissa Cowley Wolf perennially returns to what she calls a “crisis of relevancy.” She describes this “crisis” as the failure of arts and culture nonprofits to effectively explain their societal import to donors and funders, which in turn leads to underfunding of the sector. During an episode with nico wheadon, founder and principal of bldg fund, llc, Wolf shares this conclusion and asks, “How do we correct this—what stories should we be telling?”

wheadon flips this question on its head: “From where I sit, the question is less what stories we should be telling and more who should be telling them. I’m an advocate for ‘for us, by us institutions’ and think the priority within the sector should be empowering and resourcing communities to tell their own stories.”9

In recent years, various leaders in arts philanthropy have acknowledged the power that POC artists and culture bearers hold to transform the harmful dominant narratives that fuel systemic racism. As such, they have made the case for funding “narrative change” as a core arts and culture strategy for achieving social justice. This call to fund the work of POC cultures and creative communities signals a step toward greater racial equity in support for arts nonprofits.

However, this framing continues to leave the POC arts and culture community vulnerable to donor-centric paradigms, like the aforementioned “crisis of relevancy.” wheadon’s reflection challenges members of arts philanthropy to acknowledge and reconsider the metanarrative at play in their giving practices. Her assertion that POC-led arts organizations should be funded for the purpose of expressing their underrepresented narratives problematizes the notion that these narratives must be evaluated by donors and funders in order to earn support.

Additional POC guests on “The Path Forward” respond similarly to the “crisis of relevancy” by decentering donor expectations. Evolv founder Eboné M. Bishop asserts that instead of charging POC-led arts and culture nonprofits with the task of making a better case for their relevance, philanthropic institutions need to become more relevant by disprivileging Western standards of artistic merit.10

Co-founder of Peoplmovr, Geoffrey Jackson Scott, expands on Edgar Villanueva’s calls to decolonize wealth, offering, “To my mind, the landscapes of arts funding and overall philanthropy would do well to come together in service of repair and follow the leadership of Black and Indigenous folks in doing so. What I’d like to see is nothing short of transformation.”11

Both Bishop and Scott invert the “crisis of relevancy,” shifting discourse from a preoccupation with how to persuade donors and funders to increase support for arts and culture to an acknowledgment for the need to reshape arts philanthropy in service of racial justice.

These critiques echo larger calls for racial justice in philanthropy by individuals and groups seeking support for POC communities. Many engaged in this work, including members of the CCF movement, point to INCITE’s 2007 anthology “The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond The Non-Profit Industrial Complex (NPIC)” as a seminal influence. Essays from activists and academics interrogate the power imbalances within funding structures that shape and manage the NPIC, which this text defines as “a system of relationships between the State (or local and federal governments), the owning classes, foundations, and non-profit/NGO social service and social justice organizations.”12

In response to oppressive power dynamics, many community organizers and leaders have chosen to exit the NPIC. Art.Coop has documented how artists and culture bearers have also turned to alternative structures outside of the 501c3 model, such as worker-owned cooperatives, mutual aid groups, community land trusts, and other entities rooted in solidarity economics.13

Still, there are more than 120,000 US arts and culture nonprofits that continue to rely on the 501c3 tax-exempt status to secure funds for their work.14 While fundraising mechanisms within the NPIC can perpetuate the harms of systemic racism, an increasing number of nonprofit development professionals are crafting and implementing tactics and strategies that aim to confront and eradicate philanthropic redlining. In its commitment to disrupting donor-centric dynamics toward achieving economic and racial justice in fundraising and philanthropy, the CCF movement is a prominent example of this subversive approach to transforming how the nonprofit sector works.

Amplifying POC Narratives to Change the Donor-Centric Fundraising Paradigm

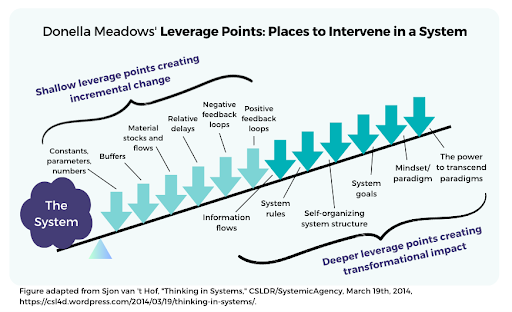

The CCF Principles are the bedrock of the movement and a natural starting point for delving further into the “why” and “how” of CCF. Understanding CCF as a systems change approach, we can interpret these principles as new community-centric rules for fundraising designed to replace the existing donor-centric rules that uphold racial inequities within the NPIC. As such, the CCF Principles correspond with number four in scholar Donella Meadows’ “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.”15 Meadows describes this fourth most influential leverage, out of a total of twelve that she speaks on, as “the power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.”16 As such, CCF engages with the NPIC as a broken system with the purpose of fixing its oppressive dynamics. Its vision for how to achieve this goal is to amplify and harness the power that fundraisers hold by cultivating community guidelines and resources that nonprofits can organize around and experiment with in their efforts to transform the NPIC into a more racially equitable system.

Exploring CCF within the arts and culture field, in particular, reveals the movement’s even deeper leverage within the NPIC. Scanning CCF literature and media, I found that POC cultural influences are a potent undercurrent within the movement. From the Afro-futurism at the core of adrienne marie brown’s Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, to the gamut of POC traditions cited in essays on the CCF Hub—such as susus and ukub17 as well as mano cambiada18—POC arts and culture serves as a clear inspiration to many in the CCF movement.

Moreover, research participants whom I interviewed spoke on the affinities between CCF and their own cultural backgrounds. Madalena Salazar, Executive Director of Working Classroom, noted that she saw a reflection of Chicano power-building practices—such as “mutual aid, giving circles, and intentional relationship building”—within CCF. Explaining further, she stated:

I was raised with the sense that we give back to our community. And it’s not just my family. Folks in my community were also raised with that understanding. And I see that in the writings of CCF. I’ve seen that, particularly, like in the writings of Nonprofit AF, these are our values. These are our cultural values.19

Although Jeremy Dennis, President of Ma’s House, was new to CCF at the start of our conversation, he told me that he instantly saw the CCF Principles’ embodiment of Native community building values, especially the tenet of keeping capitalist exchange to a minimum.

Sentiments regarding CCF’s correspondence with POC cultures were echoed by additional POC research participants. The perspectives and reference points reflected within research participant interviews and broader conversations within the CCF community suggest that CCF walks in step with a wide range of POC cultures.

Moreover, within this context, culture—inclusive of traditions, values, and norms—emerges as a central node of CCF’s work. Understanding CCF through the lens of culture brings forth the movement’s impact at yet a deeper leverage point, the second highest within Meadows’ construction of systems-level interventions: “The mindset or paradigm out of which the system—its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters—arises.”21

Research participants and other CCF practitioners have demonstrated that narrative change is an implicit praxis within the movement. Replacing donor-centrism, a paradigm supported by white supremacy culture, requires building new narratives of community-centrism, a paradigm rooted in values and histories of POC communities that CCF aims to uplift and amplify.

This approach corresponds with the above-mentioned visions for revolutionizing arts philanthropy in the face of the donor-centric trope of a “crisis of relevancy.” wheadon’s insistence on supporting the autonomy of POC communities to tell their own stories alongside Bishop and Scott’s calls for arts funders to become more accountable to POC communities point to the power that self-determined, POC-led narratives hold to transform philanthropy in the arts—and throughout the nonprofit sector—towards achieving greater racial equity.

Meadows’ highest leverage point for systems change is “The power to transcend paradigms.”22 Accepting that no paradigms are universally “true” offers the flexibility to create and use paradigms in service of a larger purpose. This understanding converges with social change praxes developed and deployed by POC scholars and activists in the US and throughout the world. Inspired by the work of Barbara Christian, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldua, Merle Woo, and many other POC feminist scholars, Chela Sandoval’s theory of “oppositional consciousness” prioritizes the act of resistance over loyalty to ideologies.

She explains, “The differential mode of oppositional consciousness depends upon the ability to read the current situation of power and of self-consciously choosing and adopting the ideological form best suited to push against its configurations, a survival skill well known to oppressed peoples.”23 This praxis requires adaptability over attachment in order to stay responsive to evolving power dynamics. Engaging with fundraising as a mode of narrative change embodies Meadows’ recommendation to transcend paradigms and Sandoval’s invitation to participate in oppositional consciousness.

CCF strategies and tactics are not fixed practices. Rather, they are responsive to the ongoing challenges presented by white supremacy culture in philanthropy. CCF does not celebrate nonprofit fundraising as the best and only way to build resources for POC communities. Instead, it leverages fundraising as a tool for changing the white supremacist mindsets, paradigms, and narratives that philanthropy often upholds.

You can see core findings from both the landscape analysis and interviews in the following five-page summary: “Key Takeaways for Nonprofit Leaders and Fundraisers.” You can also dive deeper into the full report here: Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector.

Footnotes

- For the purposes of this report, the term resource builder refers to individuals working to grow capital, capacity, and other forms of support for their organizations. As such, this term expands beyond the traditional notion of fundraising to include non-monetary modes of sustaining a nonprofit’s work.

- “Arts Funders Forum’s Research: A Look at What We Learned,” Art Funders Forum, September, 24, 2019, https://www.artsfundersforum.com/news/our-findings-2019.

- Reina Mukai, Nakyung Rhee, Mohja Rhoads, and Ryan Stubbs, Grantmakers in the Arts: Annual Arts Funding Snapshot, (New York: Grantmakers in the Arts, 2022), https://www.giarts.org/sites/default/files/2022-arts-funding-snapshot.pdf.

- Snapshot of Today’s Philanthropic Landscape, 11th Edition, (New York: CCS Fundraising, 2022), https://go2.ccsfundraising.com/rs/559-ALP-184/images/CCS_2022_Philanthropic_Landscape.pdf?aliId=eyJpIjoiRDRxM0taNmJqdTZ3QThXMSIsInQiOiJvXC9McGVIRVI1dFArd0UwUUc5Z2F1QT09In0%253D

- Charisse Burden-Stelley, Jarvis Givens, and Elizabeth Burden, Toward the Future of Arts Philanthropy: The Disruptive Vision of the Memphis Music Initiative, (Memphis, TN: Memphis Music Initiative, 2018), 66, https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2777/mmi-disruptive-philanthropy-study.pdf?1620831779161.

- Not Just Money: Equity Issues in Cultural Philanthropy, (New York: Helicon Collaborative, 2017), 5 -8, http://notjustmoney.us/.

- Eddie Torres, “Arts Grantmakers’ Changes in Practice: Present and Future,” Grantmakers in the Arts, November 5th, 2020, https://www.giarts.org/blog/eddie/arts-grantmakers-changes-practice-present-and-future.

- “2020 estimates of racial equity funding off by as much as two-thirds,” Alliance Magazine, October 6th, 2021, https://www.alliancemagazine.org/blog/2020-estimates-of-racial-equity-funding-off-by-as-much-as-two-thirds-actual-figure-far-less-finds-research/.

- nico wheadon, “The Cultural Strategist: nico wheadon,” interview by Melissa Cowley Wolf, The Path Forward, MCW Projects, April 3rd, 2021, transcript, https://www.mcw-projects.com/thepathforward/2021/3/30/nico-wheadon.

- Eboné M. Bishop, “The Cultural Change Agent: Eboné M. Bishop,” interview by Melissa Cowley Wolf, The Path Forward, MCW Projects, January 1st, 2022, transcript, https://www.mcw-projects.com/thepathforward/2022/1/4/the-x-ebon-m-bishop.

- Geoffrey Jackson Scott, “The Involvement Strategist: Geoffrey Jackson Scott,” interview by Melissa Cowley Wolf, The Path Forward, MCW Projects, August 22nd, 2020, transcript, https://www.mcw-projects.com/thepathforward/2020/8/16/gsj.

- INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence Staff, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), xiii.

- Nati Linares and Caroline Woolard, Solidarity Not Charity: Arts and Culture Grantmaking in the Solidarity Economy, (New York: Grantmakers in the Arts, 2021), https://art.coop/#report.

- “Arts, culture, and humanities organizations,” Cause IQ, accessed March 2023, https://www.causeiq.com/directory/arts-culture-and-humanities-nonprofits-list/.

- Donella Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System,” (Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute, 1999), https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/.

- Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.”

- Samra Ghermay, “Collaborative Philanthropy is Rooted in African Communal Practice. Let’s Reclaim It,” Community-Centric Fundraising (CCF), June 14th, 2021, https://communitycentricfundraising.org/2021/06/14/collaborative-philanthropy-is-rooted-in-african-communal-practice-lets-reclaim-it/.

- Yura Sapi, “4 Antidotes for Scarcity Mindset,” Community-Centric Fundraising (CCF), July 11th, 2022, https://communitycentricfundraising.org/2022/07/11/4-antidotes-for-scarcity-mindset/.

- Erika Pettersen, Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector. New York: Arts Business Collaborative, 2023. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.35756.23681

- Figure from Pettersen, Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector.

- Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.”

- Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.”

- Chela Sandoval, “U.S. Third World Feminism: The Theory and Method of Oppositional Consciousness in the Postmodern World,” Genders 18 (Winter 1993), 15.

Erika Pettersen

Erika Pettersen (she/her) roots her work as an independent researcher, strategist, and resource builder in a commitment to challenging marginalizing discourses and systems. With over a decade of experience in the nonprofit sector, the majority of her roles as a fundraiser and capacity builder have been situated at the intersection of arts, culture, and community. She has prioritized supporting Black-led, community-rooted organizations in Brooklyn, NY, such as the Youth Design Center, Haiti Cultural Exchange, and Brooklyn Queens Land Trust. Her work is guided by a wide range of educational experiences alongside her lived experiences as a woman of mixed white and Latina heritage from Queens, NY. She holds a B.A. in Philosophy from Amherst College, an M.A. in Latin American Studies from Tulane University, and a certificate in Arts & Culture Strategy from the University of Pennsylvania. She has also completed post baccalaureate coursework in Studio Art & Art History at Brooklyn College. Building on her work history and academic credentials, she published the report “Narrative Change for Racial Equity in Nonprofit Funding: An Exploratory Report on Community-Centric Fundraising in the Arts and Culture Sector” during her time as Senior Research Scientist at Arts Business Collaborative. Erika also engages in a variety of creative practices, including fiction and poetry writing, photography, collaging, and curating.

Erika welcomes you to connect with her on Instagram (@erika_pettersen), LinkedIn, and ResearchGate. If you’re interested in chatting or collaborating, feel free to send her an email. If you’d like to support her work as an independent researcher, you can send her a tip on Venmo.

Discover more from CCF

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.