By: Allison Celosia, a movement-building fundraiser and Priscilla Hsu, a money-hater

“Aren’t politicians and community organizers supposed to challenge and transform the status quo?”

It’s 2022 in the U.S., which means campaign season is up and running. If you’re registered to vote, you’re likely getting spammed by donor appeals left and right (nonpartisan pun intended!).

Experimenting with CCF values in a political space taught us that CCF values can be broadly applied to move people away from donor-centrism, moving the nexus of decision-making (ideally) closer to the values of the movement. As we moved from status quo towards radical quo as fundraisers, we found that our solutions were just reformist in nature and still limited by the larger philanthropic industrial complex. In our wildest dreams, where communities are interdependent, safe, and supported, will there even be a need to fundraise?

Personally, we can’t wait for the revolution. Let’s make the reformist quo the new status quo and stop settling for less.

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Priscilla Hsu

Priscilla Hsu (she/they) believes in radical care, Beloved Community, and us. Priscilla is on the board of the Birthworkers of Color Collective and the Arroyo S.E.C.O. Network of Time Banks, a model where time is the dominant currency, instead of federal dollars. She’s also finally trying to get paid for their care work and would love client referrals in the occupied Tongva land of Northeast Los Angeles. You can find out more at https://priscil.la/ and send money tips for their work on this piece via venmo @priskizzle or PayPal (yes, that is my rabbit).

I’m personally asking for your help, friend.

Donate before midnight… OR ELSE WE’LL KIDNAP YOUR DOG.

Okay, that last one wasn’t real, but you get the idea.

That’s why in early 2022, when we found ourselves unemployed and burnt out from the nonprofit industrial complex, we felt particularly annoyed with campaign donor spam. We kept asking ourselves, “Why are fundraisers in electoral and advocacy spaces doing the same old nonprofit-y donor-centric scarcity mindset sense of urgency nonsense? Aren’t politicians and community organizers supposed to challenge and transform the status quo?”

Fast forward a few weeks, we saw an opening to change that fundraising narrative. At least on the local level. Thanks to our own creative ambition (or bullheaded stubbornness, depending on your point of view), we were soon hired to mobilize local donors heading into our city’s June primary election, each of us working on separate but parallel campaigns. These are lessons and reflections from our community-centric fundraising journey on the campaign trail.

Being ourselves is an asset.

“We have been asked to ‘mobilize and take action now’ time and time again, yet the status quo remains. Systems and policies are still stacked against us, and we’re still waiting for change. Why would we, a progressive campaign, double down on harm in places where we actually have control?”

We’re both queer, second generation, middle-class, femme, AAPI fundraisers. We set our scopes of work to ground the campaign strategies in CCF principles, particularly in economic justice, starting with a focus on grassroots fundraising and small-dollar donors. In our communities, that meant a multi-racial, socioeconomically diverse donor base of immigrants, artists, teachers, students, movement organizers, families, neighbors, young people, people who had never made a political donation before, and so many more folks who shared and understood our lived experiences.

There were times when it felt challenging, though. Both of us worked closely with white, upper-class fundraising colleagues on our respective campaigns. Much like our experiences in white-dominant institutions in the nonprofit sector, we had hoped to show up as our full selves while fundraising but shared the same resentment when we had to codeswitch, navigate, and strategize around whiteness. We were intimately familiar with the BI&POC working-class communities that these campaigns were representing, and had hoped that the fundraising teams would reflect that as well.

Allison: I remember a particularly stressful meeting just three weeks before the election. The folks on the leadership team, including myself – because damn straight, I advocated to be on the leadership team – were discussing ideas for fundraising emails at this critical stage of the election cycle. Based on previous email campaigns I had run that embraced the unique strengths and interests of our donor base, I had pitched a two-part series that relied on levity in part one and transparency and political education in part two. My white colleagues pushed for messaging that appealed to the election countdown and sense of urgency from the get-go.

I was triggered! I took the day to calm down and came back to the team, remaining firm on my narrative strategy. I named that I felt my BI&POC femme labor around this email campaign was being misunderstood, and went on to deliver a master class (their words, not mine!) lesson on why sense of urgency just wasn’t going to cut it for our community.

“Promoting our work through a sense of urgency is harmful. I’m tired. Black and brown people are tired. We have been asked to ‘mobilize and take action now’ time and time again, yet the status quo remains. Systems and policies are still stacked against us, and we’re still waiting for change. Why would we, a progressive campaign, double down on harm in places where we actually have control?”

Mic drop. The team received my feedback. My white colleagues let go of a sense of urgency that week, and we modified the levity series for our targeted audience. I had prioritized this community-centered narrative throughout my entire time working on the campaign, focusing on the lived experiences of our donors and advocating for Black and brown dignity. Fast forward to the post-election: our campaign not only won at the polls, but we outraised the opposing campaign in every single filing period of the election cycle since June 2021. I could proudly say that I was an integral part of that success, and I did so by being unapologetically me.

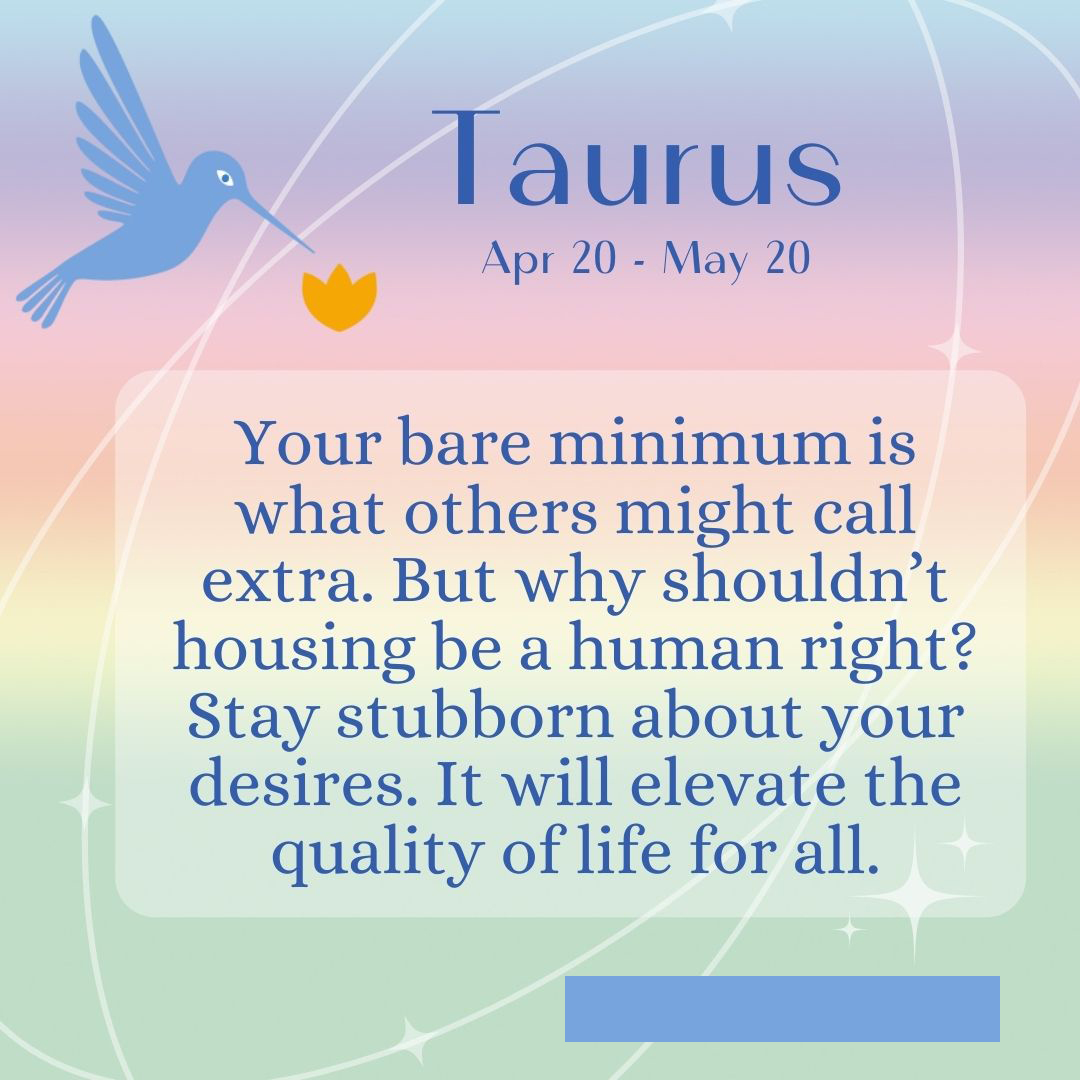

Priscilla: Likewise, as a self-identified goof, I wanted to uplift the fun in fundraising. One of my favorite projects on the campaign stemmed from the age-old question: “have you seen this meme?” I don’t have any social media accounts, but I still love when my friends include me in the meme economy, especially when they go out of their way to send me screenshots because I’ve been login-blocked. Those are friends I could easily turn to for support, whether that’s help moving furniture or help mobilizing resources towards a cause I really believe in. But those connections can be hard to keep up, which is why I wanted to create something worth sharing with friends, whether you talked last week or last year. So I made political horoscopes centered around our campaign values that I would be willing to share with my friends, and it turned out to be one of the most popular filters on the campaign account. Field staff and volunteers loved them, it was affirming to see how others shared my sense of humor, and it was work I was proud to put my name on.

The values alignment matters.

To them, I was some faceless fundraiser who was only here for one thing: money. And in those situations, they were right. I sent out transactional emails, and I received transactional responses. It didn’t make me feel good.

When we talk about progressive values, money is the last thing included. Critiquing capitalism, challenging donors, turning down money… that kind of analysis has gotten each of us in hot water in nonprofit spaces. Yet, on both progressive campaigns we worked on, we were able to operationalize many of our financial values and priorities: community relationships, self-empowerment, and wealth equity.

Gift policies were blunt, specific, and gratefully established before we joined the campaign teams. We had explicit financial boundaries: “No corporate money! No real estate developers! No big oil!” which ultimately helped open up countless creative ways to organize donors towards more values-aligned contributions.

Trial and error was definitely a part of the process. Both of us were constantly learning and unlearning what worked to connect with and retain diverse donors in our broader campaign networks.

Priscilla: One of my stumblings reminded me of the importance of values alignment to me in this work. I was asked to do some traditional email segmentation and email a list of people I was told had brushed shoulders with my candidate at some forum some vague time ago. I have no idea how you define ‘brushed shoulders with’ because most of my emails got blocked, presumably because they thought I was spam. The sting of impersonal rejection personally stung in only ways a fundraiser knows. It was like the time I sent out a generic International Women’s Day email for another job, and someone responded with disdain and a very personal ‘you should know better’ because of something they must have found on my LinkedIn. I never responded, but I was annoyed for days. How could they assume! They don’t know anything about me!

And that was the problem. These people who blocked me, who made assumptions about me; they didn’t know me. To them, I was some faceless fundraiser who was only here for one thing: money. And in those situations, they were right. I sent out transactional emails, and I received transactional responses. It didn’t make me feel good. And I’ve done the same thing in reverse. I’ve blocked and unsubscribed from numerous “personalized” political texts and emails. Sometimes I read them for fun, the way only people in fundraising communications read other fundraising comms for fun, but most of the time, I just don’t want to deal with another urgent plea to give… OR ELSE THEY’LL KIDNAP MY DOG.

Allison: In my role, upon learning the “no corporate, no developer, no oil money!” rule, I felt free to be creative about how to mobilize donors and resources. I designed a fundraising policy and strategy that not only prioritized grassroots donors but invested in their own financial empowerment as part of their contribution.

Speaking from my own experience and upbringing, I didn’t know how to manage money for years. I’m the daughter of immigrants from the Philippines, so my financial education was limited to “open a savings account” and “go to college and get a good job.”

That’s why when I solicited donors to make a gift, I gave them tools – the most popular of which was the 1% equity model. I asked donors to think about their own privilege and capacity to give and recommended the following sliding scale: If your monthly income is $1,000, donate a recurring gift of $10/month; $2,000, donate $20; $3,000, donate $30; and so on.

This model eliminated the barrier for folks who would otherwise feel shame about not being able to afford to donate. It also was a supportive reality check for those who could actually afford to donate more. And it worked! In one month, we more than tripled our recurring donor pool from 30 folks to just over 100 monthly donors, and their commitments ranged from $5/month to $114/month.

The cherry on top for me was the increased self-awareness and confidence our donors had regarding their contributions. I could not believe how many people came up to me on election night and told me, “Thank you for asking me for money.” At best, a fundraiser might hear “Thank you for raising money!”, but to be specifically thanked for soliciting them, for believing in their unique donation, I was honestly moved to tears. That’s the result of a transformative gift policy.

Everyone’s relationship with money needs to change.

Working on these campaigns pushed us to learn about our own money values and where they came from. Ultimately, we all have unlearning to do. Some of our biggest pushback came from within because the “now, more than ever” ways are just so easy to reach for.

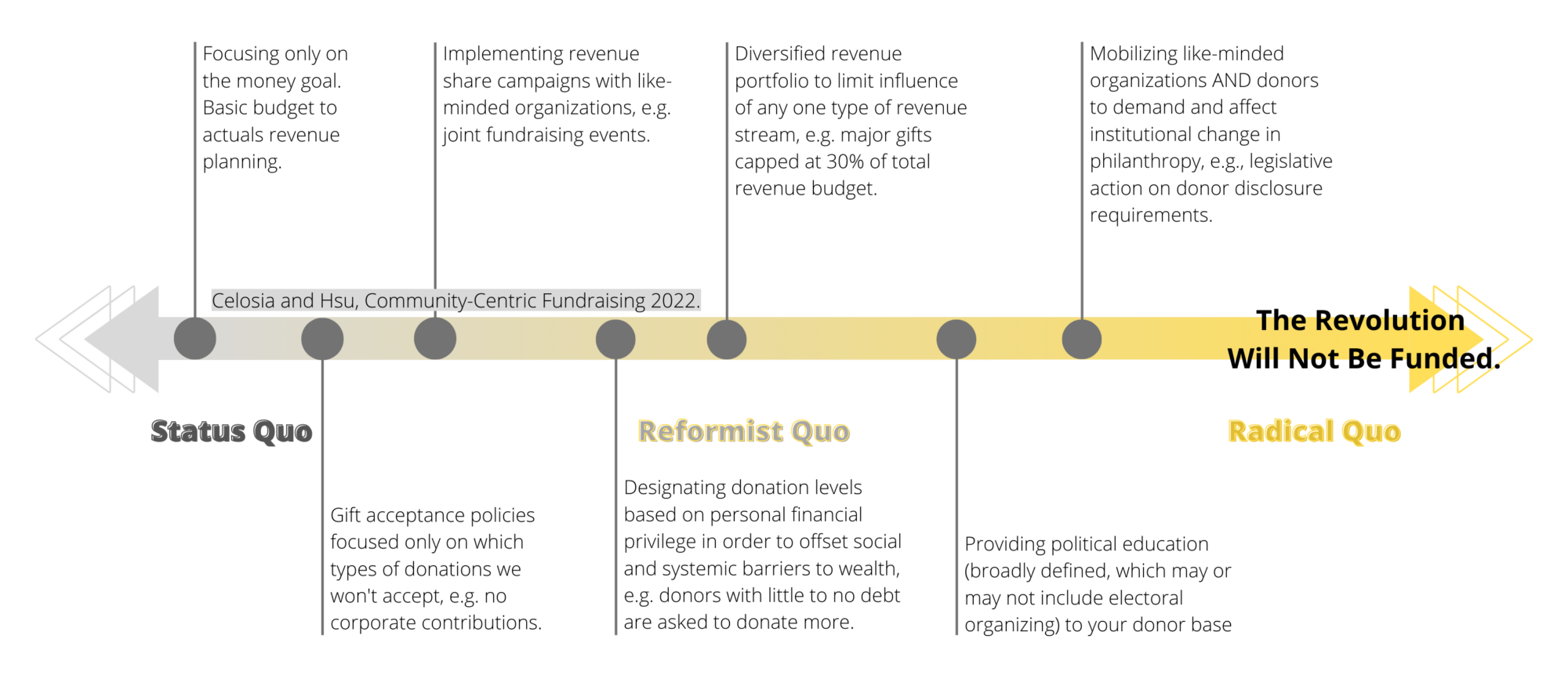

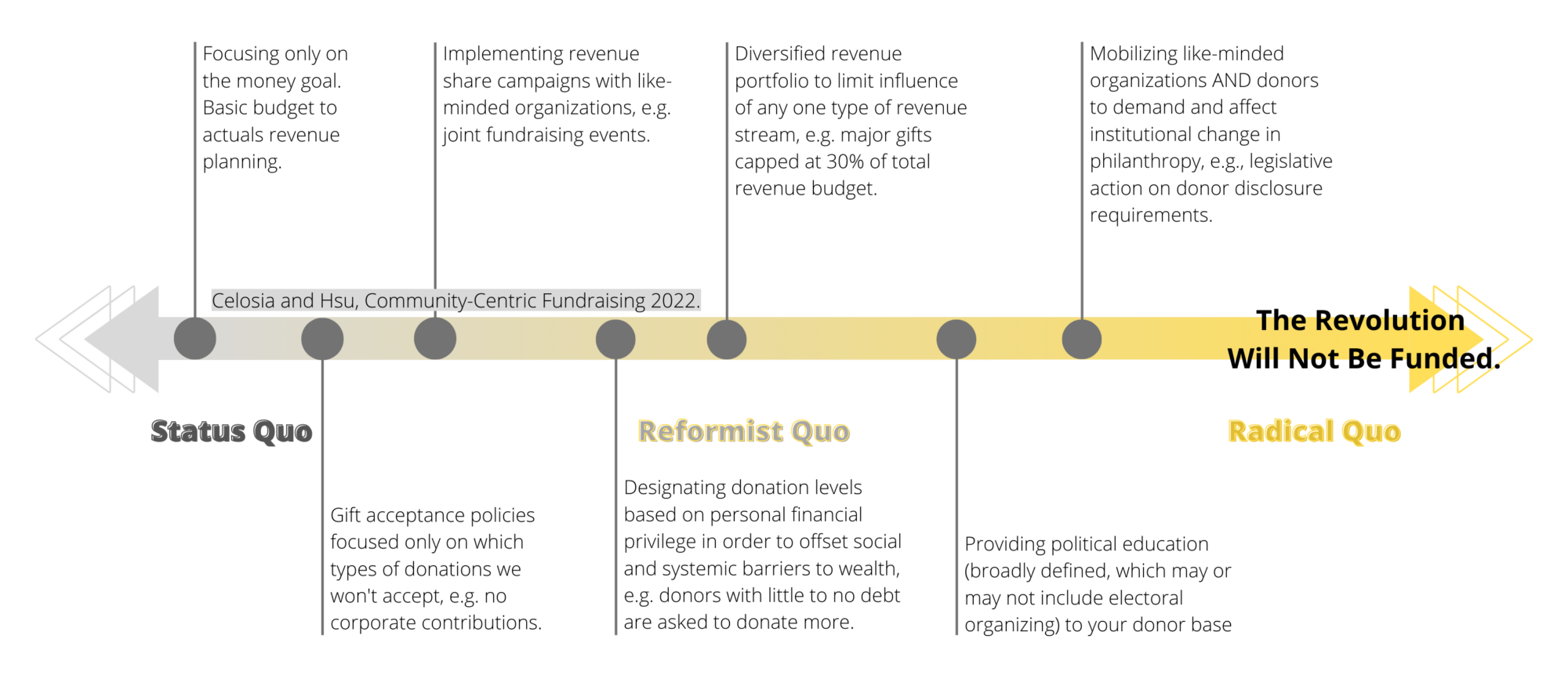

We understand that we’re reaching for a moving target in our efforts to operationalize community-centric fundraising, so we built a fundraising policy spectrum to help show what could move us from status quo towards radical quo.

Experimenting with CCF values in a political space taught us that CCF values can be broadly applied to move people away from donor-centrism, moving the nexus of decision-making (ideally) closer to the values of the movement. As we moved from status quo towards radical quo as fundraisers, we found that our solutions were just reformist in nature and still limited by the larger philanthropic industrial complex. In our wildest dreams, where communities are interdependent, safe, and supported, will there even be a need to fundraise?

Personally, we can’t wait for the revolution. Let’s make the reformist quo the new status quo and stop settling for less.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Priscilla Hsu

Priscilla Hsu (she/they) believes in radical care, Beloved Community, and us. Priscilla is on the board of the Birthworkers of Color Collective and the Arroyo S.E.C.O. Network of Time Banks, a model where time is the dominant currency, instead of federal dollars. She’s also finally trying to get paid for their care work and would love client referrals in the occupied Tongva land of Northeast Los Angeles. You can find out more at https://priscil.la/ and send money tips for their work on this piece via venmo @priskizzle or PayPal (yes, that is my rabbit).

Please, chip in $5 now!

I’m personally asking for your help, friend.

Donate before midnight… OR ELSE WE’LL KIDNAP YOUR DOG.

Okay, that last one wasn’t real, but you get the idea.

That’s why in early 2022, when we found ourselves unemployed and burnt out from the nonprofit industrial complex, we felt particularly annoyed with campaign donor spam. We kept asking ourselves, “Why are fundraisers in electoral and advocacy spaces doing the same old nonprofit-y donor-centric scarcity mindset sense of urgency nonsense? Aren’t politicians and community organizers supposed to challenge and transform the status quo?”

Fast forward a few weeks, we saw an opening to change that fundraising narrative. At least on the local level. Thanks to our own creative ambition (or bullheaded stubbornness, depending on your point of view), we were soon hired to mobilize local donors heading into our city’s June primary election, each of us working on separate but parallel campaigns. These are lessons and reflections from our community-centric fundraising journey on the campaign trail.

Being ourselves is an asset.

“We have been asked to ‘mobilize and take action now’ time and time again, yet the status quo remains. Systems and policies are still stacked against us, and we’re still waiting for change. Why would we, a progressive campaign, double down on harm in places where we actually have control?”

We’re both queer, second generation, middle-class, femme, AAPI fundraisers. We set our scopes of work to ground the campaign strategies in CCF principles, particularly in economic justice, starting with a focus on grassroots fundraising and small-dollar donors. In our communities, that meant a multi-racial, socioeconomically diverse donor base of immigrants, artists, teachers, students, movement organizers, families, neighbors, young people, people who had never made a political donation before, and so many more folks who shared and understood our lived experiences.

There were times when it felt challenging, though. Both of us worked closely with white, upper-class fundraising colleagues on our respective campaigns. Much like our experiences in white-dominant institutions in the nonprofit sector, we had hoped to show up as our full selves while fundraising but shared the same resentment when we had to codeswitch, navigate, and strategize around whiteness. We were intimately familiar with the BI&POC working-class communities that these campaigns were representing, and had hoped that the fundraising teams would reflect that as well.

Allison: I remember a particularly stressful meeting just three weeks before the election. The folks on the leadership team, including myself – because damn straight, I advocated to be on the leadership team – were discussing ideas for fundraising emails at this critical stage of the election cycle. Based on previous email campaigns I had run that embraced the unique strengths and interests of our donor base, I had pitched a two-part series that relied on levity in part one and transparency and political education in part two. My white colleagues pushed for messaging that appealed to the election countdown and sense of urgency from the get-go.

I was triggered! I took the day to calm down and came back to the team, remaining firm on my narrative strategy. I named that I felt my BI&POC femme labor around this email campaign was being misunderstood, and went on to deliver a master class (their words, not mine!) lesson on why sense of urgency just wasn’t going to cut it for our community.

“Promoting our work through a sense of urgency is harmful. I’m tired. Black and brown people are tired. We have been asked to ‘mobilize and take action now’ time and time again, yet the status quo remains. Systems and policies are still stacked against us, and we’re still waiting for change. Why would we, a progressive campaign, double down on harm in places where we actually have control?”

Mic drop. The team received my feedback. My white colleagues let go of a sense of urgency that week, and we modified the levity series for our targeted audience. I had prioritized this community-centered narrative throughout my entire time working on the campaign, focusing on the lived experiences of our donors and advocating for Black and brown dignity. Fast forward to the post-election: our campaign not only won at the polls, but we outraised the opposing campaign in every single filing period of the election cycle since June 2021. I could proudly say that I was an integral part of that success, and I did so by being unapologetically me.

Priscilla: Likewise, as a self-identified goof, I wanted to uplift the fun in fundraising. One of my favorite projects on the campaign stemmed from the age-old question: “have you seen this meme?” I don’t have any social media accounts, but I still love when my friends include me in the meme economy, especially when they go out of their way to send me screenshots because I’ve been login-blocked. Those are friends I could easily turn to for support, whether that’s help moving furniture or help mobilizing resources towards a cause I really believe in. But those connections can be hard to keep up, which is why I wanted to create something worth sharing with friends, whether you talked last week or last year. So I made political horoscopes centered around our campaign values that I would be willing to share with my friends, and it turned out to be one of the most popular filters on the campaign account. Field staff and volunteers loved them, it was affirming to see how others shared my sense of humor, and it was work I was proud to put my name on.

The values alignment matters.

To them, I was some faceless fundraiser who was only here for one thing: money. And in those situations, they were right. I sent out transactional emails, and I received transactional responses. It didn’t make me feel good.

When we talk about progressive values, money is the last thing included. Critiquing capitalism, challenging donors, turning down money… that kind of analysis has gotten each of us in hot water in nonprofit spaces. Yet, on both progressive campaigns we worked on, we were able to operationalize many of our financial values and priorities: community relationships, self-empowerment, and wealth equity.

Gift policies were blunt, specific, and gratefully established before we joined the campaign teams. We had explicit financial boundaries: “No corporate money! No real estate developers! No big oil!” which ultimately helped open up countless creative ways to organize donors towards more values-aligned contributions.

Trial and error was definitely a part of the process. Both of us were constantly learning and unlearning what worked to connect with and retain diverse donors in our broader campaign networks.

Priscilla: One of my stumblings reminded me of the importance of values alignment to me in this work. I was asked to do some traditional email segmentation and email a list of people I was told had brushed shoulders with my candidate at some forum some vague time ago. I have no idea how you define ‘brushed shoulders with’ because most of my emails got blocked, presumably because they thought I was spam. The sting of impersonal rejection personally stung in only ways a fundraiser knows. It was like the time I sent out a generic International Women’s Day email for another job, and someone responded with disdain and a very personal ‘you should know better’ because of something they must have found on my LinkedIn. I never responded, but I was annoyed for days. How could they assume! They don’t know anything about me!

And that was the problem. These people who blocked me, who made assumptions about me; they didn’t know me. To them, I was some faceless fundraiser who was only here for one thing: money. And in those situations, they were right. I sent out transactional emails, and I received transactional responses. It didn’t make me feel good. And I’ve done the same thing in reverse. I’ve blocked and unsubscribed from numerous “personalized” political texts and emails. Sometimes I read them for fun, the way only people in fundraising communications read other fundraising comms for fun, but most of the time, I just don’t want to deal with another urgent plea to give… OR ELSE THEY’LL KIDNAP MY DOG.

Allison: In my role, upon learning the “no corporate, no developer, no oil money!” rule, I felt free to be creative about how to mobilize donors and resources. I designed a fundraising policy and strategy that not only prioritized grassroots donors but invested in their own financial empowerment as part of their contribution.

Speaking from my own experience and upbringing, I didn’t know how to manage money for years. I’m the daughter of immigrants from the Philippines, so my financial education was limited to “open a savings account” and “go to college and get a good job.”

That’s why when I solicited donors to make a gift, I gave them tools – the most popular of which was the 1% equity model. I asked donors to think about their own privilege and capacity to give and recommended the following sliding scale: If your monthly income is $1,000, donate a recurring gift of $10/month; $2,000, donate $20; $3,000, donate $30; and so on.

This model eliminated the barrier for folks who would otherwise feel shame about not being able to afford to donate. It also was a supportive reality check for those who could actually afford to donate more. And it worked! In one month, we more than tripled our recurring donor pool from 30 folks to just over 100 monthly donors, and their commitments ranged from $5/month to $114/month.

The cherry on top for me was the increased self-awareness and confidence our donors had regarding their contributions. I could not believe how many people came up to me on election night and told me, “Thank you for asking me for money.” At best, a fundraiser might hear “Thank you for raising money!”, but to be specifically thanked for soliciting them, for believing in their unique donation, I was honestly moved to tears. That’s the result of a transformative gift policy.

Everyone’s relationship with money needs to change.

Working on these campaigns pushed us to learn about our own money values and where they came from. Ultimately, we all have unlearning to do. Some of our biggest pushback came from within because the “now, more than ever” ways are just so easy to reach for.

We understand that we’re reaching for a moving target in our efforts to operationalize community-centric fundraising, so we built a fundraising policy spectrum to help show what could move us from status quo towards radical quo.

Experimenting with CCF values in a political space taught us that CCF values can be broadly applied to move people away from donor-centrism, moving the nexus of decision-making (ideally) closer to the values of the movement. As we moved from status quo towards radical quo as fundraisers, we found that our solutions were just reformist in nature and still limited by the larger philanthropic industrial complex. In our wildest dreams, where communities are interdependent, safe, and supported, will there even be a need to fundraise?

Personally, we can’t wait for the revolution. Let’s make the reformist quo the new status quo and stop settling for less.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Priscilla Hsu

Priscilla Hsu (she/they) believes in radical care, Beloved Community, and us. Priscilla is on the board of the Birthworkers of Color Collective and the Arroyo S.E.C.O. Network of Time Banks, a model where time is the dominant currency, instead of federal dollars. She’s also finally trying to get paid for their care work and would love client referrals in the occupied Tongva land of Northeast Los Angeles. You can find out more at https://priscil.la/ and send money tips for their work on this piece via venmo @priskizzle or PayPal (yes, that is my rabbit).

Discover more from CCF

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.