By Allison Celosia, a #PassThePROAct fangirl and movement-building fundraiser

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

A workers’ union, in short, is an organized collective of non-management level workers who make decisions about workplace conditions, including salary and benefits, personal safety and protections, and disciplinary actions. Analyses, op-eds, and criticisms of the growing popularity of labor unions are showing up all over mainstream nonprofit media from Nonprofit Quarterly to InsideCharity to GrantStation.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Now, we are starting to see the economic shift from the Great Resignation to the Great Revolt. Strike waves and union drives are increasing in multiple industries, including in the nonprofit sector.

A workers’ union, in short, is an organized collective of non-management level workers who make decisions about workplace conditions, including salary and benefits, personal safety and protections, and disciplinary actions. Analyses, op-eds, and criticisms of the growing popularity of labor unions are showing up all over mainstream nonprofit media from Nonprofit Quarterly to InsideCharity to GrantStation.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

The revolution won’t be funded, but it should get multi-year support in the meantime

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Now, we are starting to see the economic shift from the Great Resignation to the Great Revolt. Strike waves and union drives are increasing in multiple industries, including in the nonprofit sector.

A workers’ union, in short, is an organized collective of non-management level workers who make decisions about workplace conditions, including salary and benefits, personal safety and protections, and disciplinary actions. Analyses, op-eds, and criticisms of the growing popularity of labor unions are showing up all over mainstream nonprofit media from Nonprofit Quarterly to InsideCharity to GrantStation.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

This is a huge moral shortcoming in both sectors. To ignore our own labor — as funders and nonprofit workers — is to fail at our collective mission of making the world a better place.

The revolution won’t be funded, but it should get multi-year support in the meantime

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Now, we are starting to see the economic shift from the Great Resignation to the Great Revolt. Strike waves and union drives are increasing in multiple industries, including in the nonprofit sector.

A workers’ union, in short, is an organized collective of non-management level workers who make decisions about workplace conditions, including salary and benefits, personal safety and protections, and disciplinary actions. Analyses, op-eds, and criticisms of the growing popularity of labor unions are showing up all over mainstream nonprofit media from Nonprofit Quarterly to InsideCharity to GrantStation.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!

There is no shortage of opportunities for philanthropists and nonprofit professionals to make our world a better place. Workers’ rights is a powerful first place to start, and how badass that would be to do it in the sectors whose reputations are rooted in benevolence and generosity. We can show the world we’re workers too. As we chant in the labor movement, “WORKERS UNITED WILL NEVER BE DIVIDED.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

To ignore our own labor — as funders and nonprofit workers — is to fail at our collective mission of making the world a better place.

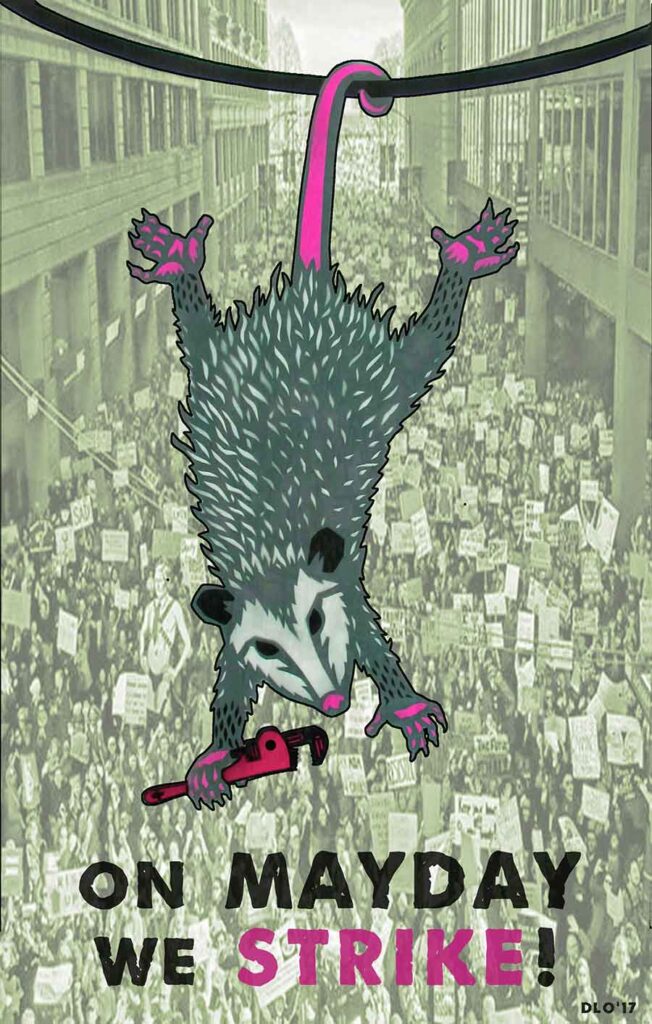

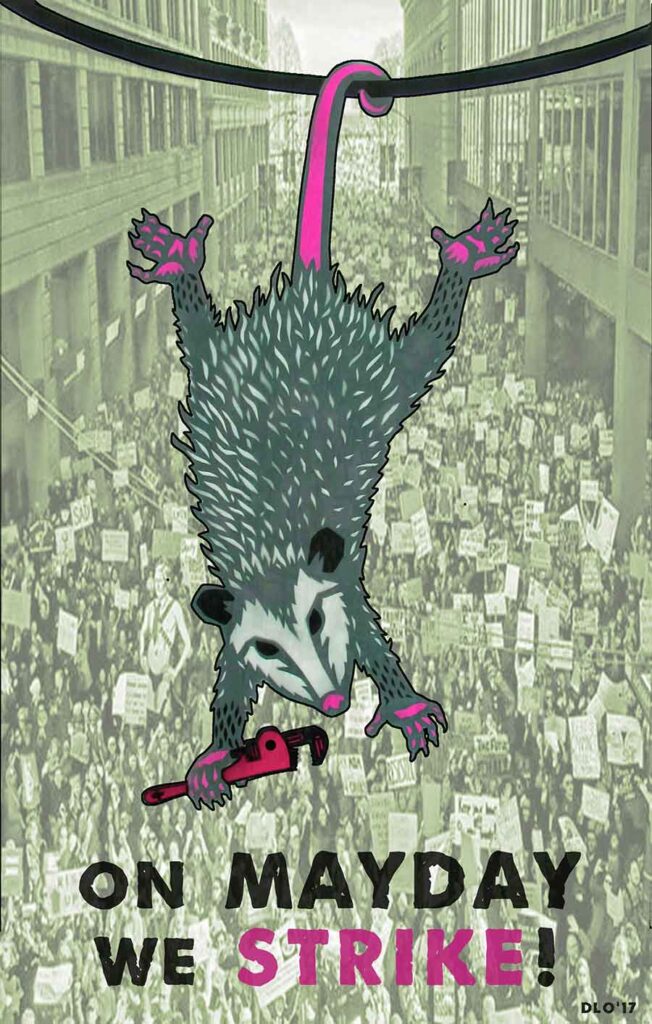

Unless you’re in a labor union or actively organizing for workers’ rights though, May Day is just another day in the nonprofit work week. In the nonprofit sector, we routinely disregard our work as “labor” until it comes to Labor Day in September, when we get a long weekend and some respite from the daily grind of programs, fundraising, and the latest version of our nonprofit’s strategic plan.

Go up the charitable sector ladder to grantmakers and philanthropic institutions, and there’s typically radio silence there, too. Funders breeze past May Day celebrations. It’s business as usual. Application reviews, board dockets, grant awards, reporting; rinse and repeat.

This is a huge moral shortcoming in both sectors. To ignore our own labor — as funders and nonprofit workers — is to fail at our collective mission of making the world a better place.

The revolution won’t be funded, but it should get multi-year support in the meantime

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Workers are fed up. In the U.S., a record-breaking 4.5 million individuals left their jobs voluntarily in November 2021 across numerous sectors and industries such as health care, transportation, food services, and others directly affected by COVID-19. It is estimated that the nonprofit workforce is still 3.7% smaller than before the pandemic, despite the accelerated demand for nonprofit services and other essential supports during this time.

Now, we are starting to see the economic shift from the Great Resignation to the Great Revolt. Strike waves and union drives are increasing in multiple industries, including in the nonprofit sector.

A workers’ union, in short, is an organized collective of non-management level workers who make decisions about workplace conditions, including salary and benefits, personal safety and protections, and disciplinary actions. Analyses, op-eds, and criticisms of the growing popularity of labor unions are showing up all over mainstream nonprofit media from Nonprofit Quarterly to InsideCharity to GrantStation.

Philanthropic media tells a different story though. A quick Google search will reveal a startlingly scant response to the newest wave of nonprofit union drives. The majority of news headlines focuses on philanthropic partnerships with the U.S. labor movement. Many recent articles still point to the 2011 launch of the LIFT Fund, a collaboration between AFL-CIO and several major philanthropic institutions including the Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations, as a primary example of this kind of movement-building work.

The absence of questioning and curiosity around nonprofit union drives reveals a missed opportunity in the philanthropic sector. Foundations hold immense economic power, and with great power comes great political influence. Short of sunsetting their own organization and distributing all funding and generational wealth by a targeted date, which would dismantle the system (one can dream!), funders can lend their powerful voice to the global labor movement in new ways — by directly supporting nonprofit unionization for all their grantees.

A philanthropist’s guide to nonprofit labor organizing

…a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives.

Consider the average grant application: mission statement, programs, outcomes, and budget. Nowadays, there are dedicated sets of questions to organizational development, staffing, and operations, such as: How many full-time and part-time employees do you have? What is the demographic makeup of your staff team? Have you had any significant changes in staffing in the past year?

These grant questions were first developed by funders with an eye on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nonprofit sector, putting pressure on grantees to diversify their staff and operations. It was the prevailing moral imperative at the time. Increased DEI initiatives would help both the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors meet their collective mission: to make the world a better place.

In that same light, a new moral imperative is upon our sector: workers’ rights and dignity. It’s time for philanthropy to support nonprofit union drives. This is a necessary step in building a just society. Anything less than this maintains the workplace status quo, and if there’s anything we all loathe, it’s the status freaking quo.

1. Applicant criteria

Scarcity mindset is inherent in the nonprofit sector, as organizations constantly compete for money. Funders are inundated with requests for resources, so grantmaking guidelines are used to filter out prospective grantees before they even apply. Nonprofit applicants must meet certain criteria such as budget size, organizational age, demographic makeup, etc. to be eligible for funding. On optimistic days, I think of these guidelines not as barriers to resources, but rather affirmative action policies that support equitable distribution of wealth.

That’s why moving forward, funders must include guidelines on workers rights. It can be as simple as sharing an affirmative statement like: “We ask whether your organization has entered a collective bargaining agreement with the staff employees. We believe a fair negotiation of workplace conditions is beneficial to the mission of our collective work in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors.” In doing so, foundations can affirm and influence the spheres of power and privilege in any given workplace.

2. Proposal questions

Grant applications increasingly scrutinize nonprofit applicants’ operations and values, particularly when it comes to building workplace equity. Funders must develop a set of questions that examine an organization’s relationship to workers’ rights. The single most powerful question funders could ask is “Are your staff employed under at-will employment?” with a Yes/No radio button, and “If yes, can you explain why?” At-will employment is the sector standard, a policy by which employees can be let go at any time for nearly any reason. By asking organizations to reflect, and in some cases, defend their use of at-will employment contracts, funders can shift the trend towards protecting workers’ rights.

The equitable alternative to at-will employment is just cause protection, which prohibits terminations without warnings or good cause. This is typically the first policy that workers seek to codify in their collective bargaining agreement as a union. In my opinion, just cause protections don’t have to be fought for from the workers’ side. Nonprofit management can step into their own power and add this policy to their handbooks to institutionalize this good-faith practice.

3. Grantee Relationships

Foundation program officers typically build relationships and rapport with the grantee’s executive director and development director. Power talks to power, and everything else is silenced. I’m challenging funders to connect with other staff members too. A lot is revealed when you talk to the most junior-level employee.

Adding more people to the conversation seems time-costly at first when all we want to do is get to program outcomes and impact. Both nonprofit and philanthropic sector employees are inordinately busy, no doubt about that, yet when we reimagine our relationships to the work grind and to the people we spend 40–50 hours a week with, this call to action is a reasonable request. It is imperative to reflect on self and community, especially when we all have agreed to work in these sectors.

Ain’t no power like the power of a union to change philanthropy

Taking these first three actions would mark a radical shift in philanthropy. Whether the funder belongs to a large national private charity or represents a small family foundation, the tactics can be scaled up or down to support both the foundation and the grantee portfolio. It may even call into question the workplace conditions of the philanthropic sector, and personally, I believe that’s a good thing!