By Allison Celosia, A #PassThePROAct fangirl and movement-building fundraiser

Imagine this: It’s grant deadline day. You get on the grant portal to submit your materials. Proposal, check. Project budget, check.

You scroll down the list of required attachments. Wait a second, what’s this? Staff and board demographics… you must’ve forgotten, darn it.

So in a rush, you scroll through the current staff and board rosters and hastily assign demographics to them “to the best of your knowledge” according to the survey categories. Save and submit. Phew!

You’re done, right? And you feel… just okay about it.

Feels familiar, huh? But doesn’t it also feel… wrong?

Identity politics… in a grant proposal?

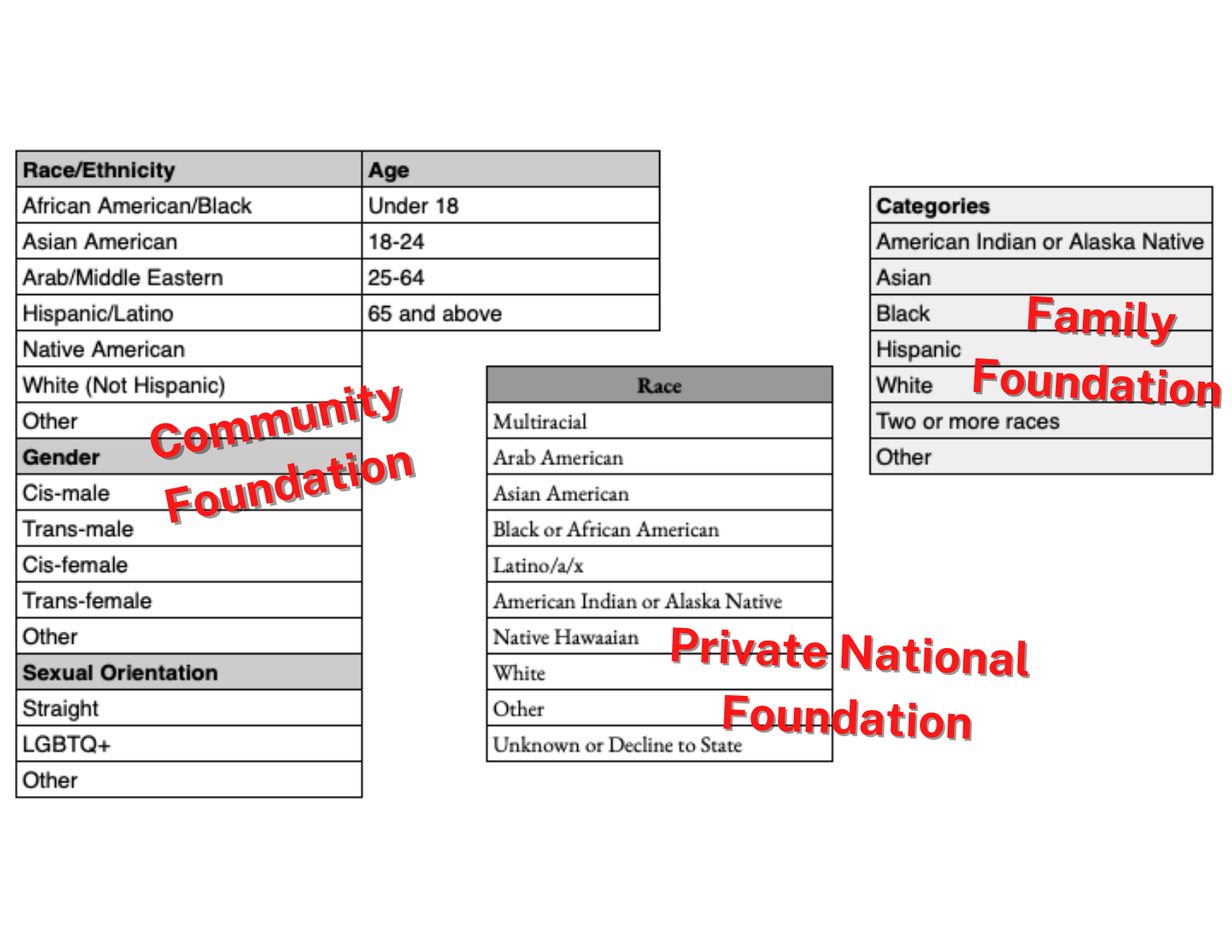

Screenshots of three different demographic surveys, which list a range of demographic categories, including race, gender, sexual orientation, and age. The answer options vary. For example, you may answer one of the following for race depending on the survey: “Native American” or “American Indian or Alaska Native.”

For most grant managers, the demographics survey is just another attachment to check off in a long list of complex documents needed to finalize a grant application. By the time we get to it, we’re tired, cranky even, at that point in the proposal process.

Nevermind when we actually sit down and look at the survey, that’s frustrating too. Nearly every funder has their own version of this survey with varying categories and formats. Most surveys will ask about race and gender, and increasingly we’ve seen questions regarding sexual orientation, disability, income, age, country of origin, language, and more.

Hastily filling out the demographics survey last minute skips an important step, one that is embedded in research design for good reason: informed consent.

Dig in deeper, and the survey response options are often wildly inconsistent. Or worse, limited in choice. For instance, are there only “male” and “female” boxes for gender? Is there just a box that says Hispanic and not Latinx? Does the option for “other” even leave space for explanation? Yikes!

The simple task of filling out a demographic survey suddenly becomes an ethical clusterfuck on how to present the whole, honest self of each staff and board member, especially if they identify with multiple marginalized identities.

Tempting as it may be to just get the survey done and out, there is value in taking time to collect and review staff and board demographics. On a surface level, these surveys provide nonprofits and funders insight and accountability on building diverse workplaces, ones that represent the very communities we work with. On a deeper level, though, they affirm the lived experiences of our staff and board. It’s a powerful but often overlooked opportunity to show solidarity in the workplace. If we are required to report on demographics to our funders, let’s do so respectfully and thoughtfully to honor the full humanity of our colleagues.

Asking for permission: Who are we?

Embracing our abundant identities requires honest communication and understanding. Hastily filling out the demographics survey last minute skips an important step, one that is embedded in research design for good reason: informed consent.

Is collecting informed demographic data a waste of time? Well, let me phrase it this way: Is respecting people’s identities a waste of time?

In one simple definition, informed consent is the practice of letting folks know what data is needed from them, how it’s going to be used, and asking for their permission to use said data. This practice has its origins in medical and scientific research in the mid 20th century. It has since become standard procedure as part of a clinician’s ethical responsibility to the patient and/or participant in a research study: People have to say yes before any treatment or experiment is conducted.

Nowadays, establishing consent is the ethical norm across a growing number of fields and social contexts to ensure equity, accountability, and safety for everyone involved. The nonprofit and philanthropic sectors are no exception.

Admittedly, prioritizing demographic data doesn’t come easily. Consulting staff and building in consent processes take an inordinate amount of staff time and resources when (let’s be honest) funders glance two seconds at the demographics, if they even look at all.

Given that capitalist reality, isn’t collecting informed demographic data a waste of time? Well, let me phrase it this way: Is respecting people’s identities a waste of time? When we ask ourselves that question, we’re more open to change, and hopefully, we’ll move quickly and operationalize collecting staff and board demographics with an inclusion and equity lens.

HR is your friend for demographic data

One example of buddying up with HR comes from my collaborative demographic survey project with Ever Galván (they/themme/elle), People and Operations Director at Californians for Justice Education Fund (CFJ). CFJ is a statewide youth-powered organization fighting for racial justice. The staff historically has been a multiracial, multigenerational team, with 88% of the leadership team identifying as Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BI&POC) and 100% of program staff identifying as BI&POC. Embedded in the organization are deep values of Black liberation, equity, and political education.

At the time of the project, I was Development Manager in charge of grant writing and foundation giving. I was up to my eyeballs in proposals and reports, and there I saw it: another demographics survey.

I had already wrestled with incomplete staff data in a previous submission. This time, I wanted to be more intentional about reporting demographics.

I reached out to Ever for help. I knew they were collecting similar data to support recruitment and retention strategies for a diverse staff team. This way, we could share the work of collecting employee demographic information. It actually was a cool opportunity to challenge ourselves creatively: “What if we could embody inclusive community practices around demographic data and identity politics? Just imagine the possibilities!” we exclaimed. (We’re nerds for DEI and data. Can you tell?)

Fast forward through two weeks of research sharing and co-writing several different drafts, we came up with a staff demographics survey that would meet both our departments’ needs.

The decision points were so thoughtful, for example:

- We disrupted the gender binary, so no respondent would feel pressured to answer with their assigned-at-birth gender. Instead, the drop list embraces fluidity. Ever’s favorite of the options is “Woman/Man (non-cisgender).”

- On race, gender, and sexual orientation, we made sure to rename the Other option, so no one would feel erased. It’s now called “None of the above, will specify below” with a short text field for explaining. I particularly love the freedom to claim my Bisaya roots.

- We affirmed and prioritized our staff’s personal safety and anonymity in disclosing their information by inviting respondents to be expansive and share as much or as little as they wanted in order to feel safe in the process.

- We even took a political stance upon feedback from our colleagues. In naming Middle East North Africa (MENA) as one of the race categories, we included a descriptive list of countries covered by this region and intentionally listed Palestine, and not Israel. As a racial justice organization, we knew it was the right move for CFJ. I share this to demonstrate that it sometimes takes discomfort and generative conflict to land an organizational values-driven decision like that. And believe me, there was a lot of discomfort.

Still, there was more to do to make this data work for fundraising. How the heck would I answer a limited format survey from our funders? What if the identities our staff held for themselves weren’t listed or recognized appropriately?

Insert honest solution: informed consent!

In the opening paragraph at the top of our survey, I explained, “As part of this data collection, the Development team will be periodically sharing results with our funders. With your consent, we may recategorize the data to fit the strict guidelines of their survey form. It is our intention to represent your identity safely to our funders.”

I acknowledged the harm involved, and formally asked for permission. If staff members disagreed or had questions, I encouraged them to speak with me directly. This humble request made all the difference.

We presented the demographics survey at an all-staff meeting. Our colleagues felt validated in their identities and informed about the process. Many staff thanked us for designing such an inclusive survey. They appreciated our transparency, saying, “I had no idea this was part of your job, this really means a lot.” It was a great success!

Ever and I wrapped up the project soon afterwards, tying up a few loose ends for internal control. The staff survey results would ultimately be held confidentially in People and Operations, aka HR. The Development team would have access to a disaggregated, anonymized table of results that would be updated every six months with the support of the People and Operations team. Then, the Development team would be solely responsible for collecting and updating board demographic information in a similar process. Finally, the two teams would review the policy and procedure annually to make changes as necessary.

The missing data set: funder diversity

That is why I am calling for a fundraising world where demographic information flows both ways … Navigate challenging conversations through mutuality and, most importantly, informed consent.

This project really felt like the best of both worlds: operationalizing a core job responsibility and validating the humanity in our work. Yet, the process left me wanting more, particularly from our funders. Who are they? What is their staff and board diversity like?

Nonprofits are constantly asked to provide demographic data, but rarely do we receive the same information in return. If staff and board demographic surveys were designed to promote diverse workplaces in the nonprofit sector, to ensure programs and services were being led by people from the community, can’t we ask for the same from philanthropy? Are grantmakers similarly representative of the people and communities served? The short answer is no.

That is why I am calling for a fundraising world where demographic information flows both ways. Build it into the grant agreement. Invite both the foundation and grantee to report annually on diversity. Navigate challenging conversations through mutuality and, most importantly, informed consent.

This level of transparency and trust will only deepen the funding relationship. Our shared humanity belongs in these spaces, funders and fundraisers alike. We’ll be able to understand our partnership in the movement all the better when we can be our full selves together.

P.S. Here’s a gift to the CCF community: an open-source version of the CFJ staff demographic survey. Feel free to adapt accordingly for your own demographics survey with source credit to “Adapted from Informed Consent Demographics Survey. Source Credit: Allison Celosia and Ever Galván, Californians for Justice Education Fund (2021).” Thanks!

Allison Celosia

Allison Celosia (she/they/siya) is abundant. Based on unceded Tongva land, they are a fundraiser and a steward for economic justice. She is a second generation Bisaya American and the proud daughter of immigrants. Allison’s professional path is deeply rooted in the nonprofit sector. Outside of fundraising, Allison is active with local labor organizing. She encourages softness as a strength. They also mill their own flour and do a lot of home baking projects. Connect with Allison on LinkedIn and Twitter. Readers are welcome to drop some community love at Allison’s PayPal for her labor on this piece.

Discover more from CCF

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this thoughtful and engaging piece! I also appreciate the callout to foundations. Seven years ago Dorceta Taylor published a nationwide review of “The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations” and since then Green 2.0 has published several “Report Cards” to follow up on these data. Here’s a quote from the 2019 Report Card: “It is shocking in 2020 that organizations would resist demonstration of commitment. Of note is Pew Charitable Trusts, with a budget of over 366 million dollars, which claims to be a ‘major force in educating the public and policy makers about the world’s most pressing environmental challenges,’ but has so far refused to participate in the survey despite Green 2.0’s numerous appeals.” Green 2.0 has apparently received a bit more data for the 2021 Report Card, but still very limited (see here: https://diversegreen.org/transparency-cards/). Thank you again for shining some light on this!

Thank you for your thoughtful reply, Sean. That’s fascinating about Pew. I’ve seen different iterations of diversity transparency cards, and I hope the results of this Green 2.0 version provide opportunities for greater reflection and inclusive practices moving forward.

This is so amazingly timely for our organization. We have been trying to find a solution to collecting board demographics for various reporting purposes and really struggling since, as you note, the expectations for reporting are exceedingly limited and problematic. I think that the way you acknowledged the need to reorganize data and asked for permission to do this was really smart and an example of creative problem solving. We will most definitely be looking at your demographic survey. Thank you!!

Amazing, Laura! So glad that my essay was a timely read for you and your organization. I really like the simplicity of asking for consent. It builds trust and helps move the work forward. Good luck with the board data collection!

Thank you for sharing! We implemented a similar (if not quite as comprehensive) survey at our organization. And, we also want funders to disclose their demographics to us – especially the ones we know are virtually all-white. It feels so inequitable to have that flow of information be only one-sided.

That makes my heart sing, Lizzie! Survey design is both a nerdy and heart full exercise, so that’s awesome to hear about a similar survey at your organization as well. As for the funder demographics, I’m hopeful it’s part of the relationship building I can experience with colleagues in both the grantmaking and fundraising communities. Let me know how conversations go in your networks if you have the chance.

Well said, Allison, and thank you for putting what must have been a huge amount of effort into creating an equitable survey. Since funders do not use your categories, I’d love to know more about how you shoehorned your data into their format while staying true to your intentions. No easy task, I’m sure.

Also, you really hit home with “… (let’s be honest) funders glance two seconds at the demographics, if they even look at all.” This is just one of many ways that funders make us nonprofits jump through hoops for no reason. Why are they asking if they don’t really care? While we’re asking them to report back to us about their demographics, perhaps we should also ask that they aggregate the data they are receiving and feed it back to the nonprofit community. I would be fascinated to see this kind of data for our sector.

Thank you, Hillel, for your reflection! I’m really glad this essay resonated with you.

As for using our data collection to fulfill the funder requirements, it goes back to the informed consent framework. In the case study example of CFJ’s internal demographic survey, I asked each staff respondent to give me permission to “recategorize” their responses and to get back to me if they had any questions. One staff member did reach out, and we discussed how their specific identity might roll up into different and more commonly used demographic umbrella terms, e.g. Latinx, AAPI, Middle Eastern. It was a thoughtful discussion, and we both acknowledged the limitations together. Looking back on this interaction, I think the 1:1 conversation approach worked here because at the time, the staff size was quite small (only 1 of 30 employees had follow-up questions). For larger organizations, I’d probably approach it a little bit differently.

And yes! I feel that, the hoops. It’s a good starting question though — try it with a foundation program officer that you trust and have a good relationship with: ask them “What do you do with our staff/board diversity information?” See where the discussion takes you! (And tell me what happens! Haha!)

Hi, Allison, thank you so much for sharing this! I had a similar experience developing a staff demographic survey, and approaching the task with care really opened up relationships and conversations among the team. I felt honored by my co-workers’ trust.

More recently, I’ve seen a rise in requests for board demographics, but ran into serious roadblocks when I attempted to roll out the same approach there. A gatekeepers said the request would offend board members–even though we sought the same information from staff and participants.

I’d love to know if you or others have successfully gathered board demographics, as well as your approach. Thank you!